Anchoring bias

The cognitive bias of anchoring is when your decision is influenced by the first thing you heard, saw, or read. It is the reference point or anchoring point on where your future decisions are made.

Let me give you a simple example. You want to buy a plain cup of coffee to go from a cafe. When you first started drinking coffee in college, a cup of coffee was about $1 or less. You gave up coffee for 10 years. Starbucks and other premium coffee brands arrived. Then you decided to drink coffee again and went to Starbucks. You are shocked that a cup of coffee is now $3 or up to $6 for a latte.

You might say, “I would never pay $6 for a cup of coffee” and storm out. Why are you surprised and mad? You are anchoring on that first cup of coffee you bought long ago and believe that coffee should not have gone up in price so much. In reality, the quality has improved and coffee is not a commodity anymore.

Anchoring in investing

In the investing world, anchoring happens when you purchase a stock and anchor on the price and the circumstances at the time of purchase. Why is this bad? Isn’t that the way you calculate if you gained or lost money? Yes, that is true, but it may prevent you from making good financial decisions in the here and now, instead of what you paid in the past.

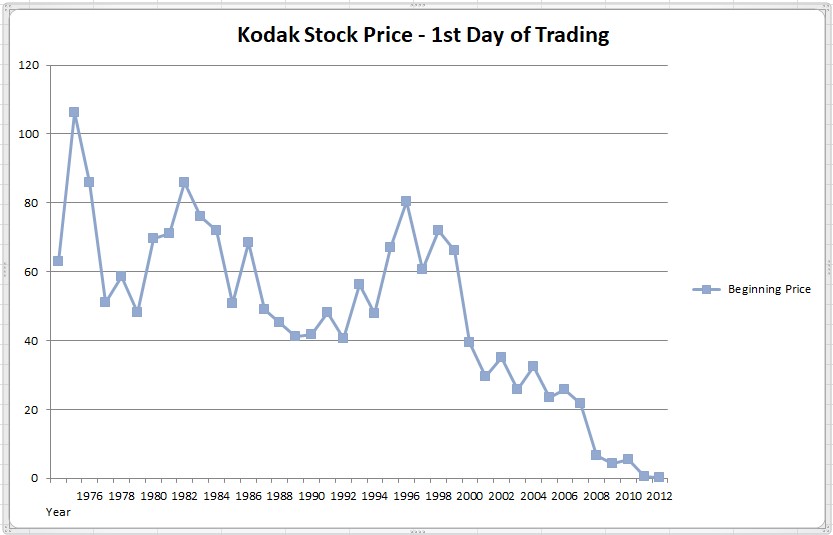

Let’s look at two examples of a gain and a loss position. We will look at Kodak’s stock price in the 1990s to 2000s.

Anchoring on a gain

For the first example, suppose you bought 100 shares of Kodak stock on the first day of trading in 1993 at a price of $40.50/share for a total investment of $4050. At the end of 1998, your shares soared to $72/share for a gain of $3150 (78%). You are a genius! You now think, “Let it ride” and keep it in Kodak. A reasonable decision if you did not research what was happening to film cameras.

However, digital cameras were becoming more and more popular moving from professional photographers to consumers by the mid-1990s. Even though Kodak produced some digital cameras, their main business was still film. This should have been a big concern in 1998.

Anchoring is based on the past. For your Kodak stock, you anchored not only on the price of your purchase but the reasons you purchased the stock in the first place. Since 1993, photography technology changed dramatically, but if you didn’t really see that and how it affected Kodak, all the information you based your current decision on was what you remembered from 1993. Your anchor was in 1993 but the current situation is dramatically different.

So in late 1998, you should have looked at Kodak and said to yourself, if I had $7200, your current Kodak investment, would you invest in Kodak at this time? The answer may have been No because of what we mentioned above.

Besides anchoring, there are also other psychological biases in play:

- Confirmation bias – You did research Kodak in 1998 but because you made so much money on Kodak, you “love” the stock and only looked for good news on Kodak. You only accepted the good news of Kodak selling digital cameras but disregarded the bad news that most of their revenue was in film.

- House money effect – Since you already made “free money” or as they say in gambling, “house money”, you didn’t feel that $3150 is really your money, so you may be riskier with that house money than the original $4050 and hence kept it in Kodak.

- Overconfidence bias – Because you were a genius buying Kodak in 1993, you know what you are doing and all the analysts and critics of Kodak are wrong, so you keep your full stake in Kodak. You have overconfidence in your stock-picking abilities.

Anchoring on a loss

Our second example is anchoring on a loss. Supposed you held on to Kodak and only look at the stock again in 2002, when the beginning price was $29.43/share. Oh, you lost $1107, so what do you do? If you are anchored to your price and information from 1993, then you would probably keep the stock and hope that it does back up to break even or have a higher gain.

You have disregarded all the information on Kodak and cameras in general. In fact, phones started to have cameras too around this time which put an end to film for Kodak. You also see that Kodak has not made good company decisions on their future.

In this loss situation, besides anchoring, you are also affected by Loss Aversion – Trying to stall or prevent the feeling of loss, of money, of your self-esteem for picking the wrong stock or not selling sooner.

Forget the past to gain more

Anchoring bias is all about the past; past price, past information, and past feeling or emotion. If you truly want to focus on better investing and having better gains do these things:

- Be in the present. Forgot why are first bought the investment, what price it was, and what information you used at that time. The current amount in that investment is what matters, then ask yourself, “Would I buy this stock now?” and “Are there other investment opportunities that are better for me now?” Your answer could be to keep your current investment but at least you though about it in the present.

- Swallow your pride. You are not a genius stock picker and selling for a loss does not make you a loser. Removing pride makes you more rational and allows you to really focus on the reasons you are investing…to make more money for retirement, the new house, and college for the kids.

- Review investment periodically. Good investors review their investments periodically due to changes in the investment price, company information, market dynamics, and personal and family changes; i.e. marriage, retirement, remodeling, etc.

Check out some of the other related blogs: