Fun behavioral games to annoy friends

Playing games is the best way to show how behavioral biases affect your financial decisions.

Let’s get started…

What do you want to play?

Commitment Game

To succeed in athletics and in life, commitment is tantamount to success. You need to be committed to the cause, to the company, and to the team. However, commitment can also blind you from new information that shows your current path is wrong. The more you commit to something, either time, resources, or money, the harder it is to end that commitment, even if it is bad for you.

What you need:

- 8 or more players

- $20 bill for you

The game:

I learned this game from the book Sway by Ori Brafman, who wrote about a Harvard professor, Max Bazerman, who taught a negotiation class. The game is an auction for the $20 bill. At the beginning of the game, you hold up the $20 bill and say, “You are auctioning off this $20 with starting bids at $1, and bids are in $1 increments. The highest bid wins. However, the 2nd highest bid needs to forfeit his bid to me. So if the highest big is $12 by person A and the second highest bid is $11 from person B. Person A wins the $20, but person B needs to pay $11 to me.”

The rational outcome:

The bidding should continue until it reaches a bid slightly under $20 because who in their right mind would bid over $20 for a $20 bill.

The real outcome:

Because the 2nd highest bidder needs to pay, this changes the game. Everyone starts bidding at the beginning until the bidding gets to the $12-$16 range. Then, normally, everyone drops out except the two highest bidders who continue bidding and get locked into their commitment. If one bidder bids $17, the next one who bid $16 doesn’t want to lose $16, so he bids $18, and so on back and forth. No one wants to lose, but as they continue bidding, their losses get large and larger. In the Harvard class, bids have gone over $200 for a $20 bill. After the game, if you make more than your $20, you can keep the money, or you can say you will donate it to your favorite charity.

The reasoning:

Commitment bias is strong as you go up in the bidding. You are also bidding in a public setting, so giving up makes you look weak, so you keep bidding higher and higher. Loss aversion also sets in, and you don’t want to feel the pain of a loss after playing this game. When you get close to $20 in the bids, you know you should not bid higher than $20 because that is a bad rational decision, but some people will do it to win and not feel the pain of a loss and are committed to winning.

The discussion:

After the game, you can discuss how the players felt at three points in bidding; when the bids started at single dollars, at $12-$16, and close to $20? Then ask the two last bidders how they felt? Did they feel like they didn’t want to lose? Did they feel they were committed to this game and needed to win?

The effect on finance and investing:

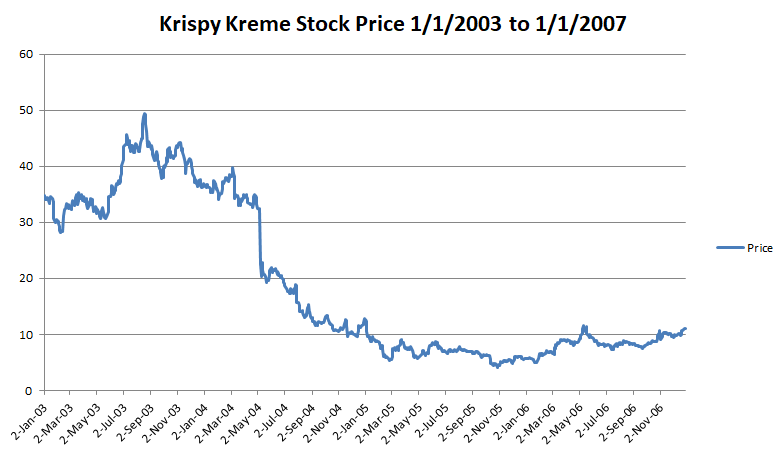

You probably have heard the term “Throwing good money after bad.” The term means wasting money on something you already spent money on that was no good. Suppose you loved Krispy Kreme (KKD) donuts and saw they were expanding like crazy, and their stock price was going up and up. You started buying their stock regularly for years. Then 2004 came, and low-carb diets became a fad. Donuts are bad. Carbs are bad. Keto diets are good.

You start seeing your KKD stock go down, but because you have so much invested in KKD, you see this as a buying opportunity and buy more. KKD has given you so much profit you are committed to KKD even when the health-conscious public has said they want lower carb foods, and the company is warning of this change. What happened? You lost all your profit and your initial capital as the stock plummeted from highs of $48.92 on Aug 20, 2003, to a low of $4.05 on Oct 27, 2005.

You might say, but you told me to buy on the downturn to cost the average of my stock price. Yes, but that is only if the company’s market did not change and the customer base did not shrink. Krispy Kreme’s customer base shrunk dramatically in 2004 with the low-carb diets.

Personal story:

Have I been so committed that I lost all my capital in a stock? Yes. In my earlier days, I would purchase much riskier stocks, or what you might call penny stocks, and look for bargains. These were rollercoaster rides. I remember a startup biotech stock I purchased at around $5 per share, which went up to $20 per share, and I rode it up. Then they had issues with their Phase 1 trials, and the stock dropped to $9 per share. Because this company only had one product, this Phase 1 issue was huge. I should have taken my $4 in profit per share, but their news and company announcement was very optimistic, so I bought more. In the end, this company’s stock we delisted as it was lower than $1 per share and eventually went bankrupt. I was committed and felt like I knew more than everyone else as I was following the news and announcements from the company, so overconfidence bias also led to this mistake.

Endowment Effect Game

The endowment effect is when people demand more to sell an object than they would be willing to buy.

If you have seen the Wolf of Wall Street movie, you remember the scene where Jordan Belfort is giving a seminar and ask a man in the audience, “Sell me this pen.” This game is about selling a pen.

What you need:

- 6 or more players, the more, the better

- Enough nice pens ($1 or more per pen) for half the players Don’t tell the players how much the pens cost.

- Have everyone bring $5-$10 in one-dollar bills

The game:

Give half of the players a pen that they can keep or sell. Have the pen owners look closely at the pen and its styling, how it writes, the smoothness, or uniqueness.

Ask the other half of the players if they want to buy the pen from the players with the pens. If they want to buy a pen from another player with a pen, they would have to negotiate an acceptable price. Give them 15 minutes to negotiate and do any buying or selling. Pen owners do not have to sell their pens, especially if they are not given a price they want.

The rational outcome:

This is a pen exchange market. If this is an efficient market, you should have about 50% of the people selling their pens, and you will find a clearing price for selling a pen, i.e., an average price they would pay to buy or sell a pen. An efficient market means everyone is acting rationally and in their best interest, and all information is known about the transaction.

The real outcome:

You find that not many pens are traded because the pen owners will demand more than what the buyers are willing to pay. You may also see that the clearing price is higher than the price you purchased the pen for.

The reasoning:

The pen owners do not want to part with the pen because they don’t want to feel the pain of giving up the pen.

The discussion:

After the game, you can discuss how the players felt in the negotiation. Did they feel pain in selling an object they own? Why didn’t the buyers offer more? Was there a difference in how they valued the pen when buying it and if they owned it? Then you can tell the whole group how much you paid for the pens and see their reaction.

The effect on finance and investing:

The endowment effect also causes people to not sell stocks or objects they own because they want to avoid the pain of loss even when, rationally, this is the best path forward. Or they demand a higher price than what the market will bear, i.e., marketing clearing price. You can see this when someone sells a house. The seller demands more than what the buyer is willing to pay due partially to the pain of loss. And if you lived in a house for a long time, there are so many memories that the pain of loss is large.

Personal story:

My son is almost paralyzed by this endowment effect. He will not give up anything you have given him, even for any amount of money, new toys, or games. The pain of giving up a toy, even a baby toy, is too much. I joke he is becoming a hoarder. This is one of the reasons some individuals hoard more than others, due to how much pain they feel from letting go of an object.

Fairness Game

What is fairness or fair value? It is difficult to decide what is fair. What is fair to me may not be fair to you.

What you need:

- 4 or more players

- Ten 100 grand chocolate bars per pair of players (or use another fun object to represent $1M dollars)

The game:

Pair up the players. Half of the pair leave the room and ensure they are out of earshot as you tell the players in the room the following: You have just come across an inheritance of $1M, but the stipulation is that you need to share this inheritance with your partner in the other room. The only way to get the money is if you agree on how to split the money between you two. If you cannot agree, then no one gets the money. You will have 15 minutes to negotiate and come to an agreed-upon split.

Now you go to the other room and tell the other half of the players the following: Your partner in the other room has a $1M inheritance, but they cannot get the inheritance unless they give you some of the money and you agree to how much you get. Remember that the money is your partner’s inheritance and not yours. You have 15 minutes to negotiate and come to an agreed-upon split.

After your instructions, you invite both groups back together to negotiate their split. They come to you to tell you the results when they have completed their negotiations or cannot complete them after 15 minutes.

The rational outcome:

The non-inheriting partners should be open to taking any amount of money. $1 out of $1M is more than they would have gained before the game, so rationally, any amount above $0 should be acceptable to the non-inheriting partner. Besides, the money is really not theirs.

The real outcome:

You will find that the split will be close to 50/50, or they will not come to an agreement. If they agree, they can split the candy bars per the agreement.

The reasoning:

The inheriting partner feels that the money is theirs and that giving anything up to the non-inheriting partner is unfair. The inheriting partner will probably offer less than 50/50 because they feel the non-inheriting partner has no right to the money. They will also think that any money they give the non-inheriting partner is more than they would have gotten anyway. They feel any money they give away is a loss since they feel they are starting at $1M.

The non-inheriting partner will think it is unfair if they don’t split the money evenly, so both partners profit the same, even though the inheritance is not theirs. The non-inheriting partner may feel some negotiating power because no one gets the money if they do not agree. For the non-inheriting partner, he doesn’t care if he gets any money if it is not a fair split because he is starting from $0. He does not feel any loss if he comes out of this game with $0.

The discussion:

After the game, you can discuss how the players felt in the negotiation. How did the inheriting partner feel about splitting the money? How did the non-inheriting partner feel about what is a fair split? Talk about fairness in this game? Why shouldn’t the non-inheriting partner accept a less than 50/50 split, as they are starting off at $0 money?

The effect on finance and investing:

If you are negotiating for anything, you should look at the lens of fairness. Is the agreement fair for you? You also need to look at the other person’s perspective and see if the deal is fair to them. Then, you can come to a better agreement. There is no “fairness meter” in life.

Suppose you are selling a 1967 mint condition convertible Ford Mustang. You rebuilt this car, finding all the parts, putting them together, and making it look great. You feel it is in excellent condition. The average price at auction for a car like that is $47,500. Suppose a buyer comes to you and offers you $55,000 for the car. You would probably take the offer and think you priced it too low or the buyer paid too much. Was this transaction fair? I would say it is very fair for both sides. You sold the car for more than you wanted. The buyer valued the car higher than your price.

Personal story:

I’m embarrassed to admit this and feel very bad about this story. In 2000, my wife and I went on a tour of China. At every tourist stop, hawkers sold postcards for $1-$5. We had been on the tour for about a week, and I was getting used to negotiating for everything, from the price of a bottle of Coke to a Chinese watercolor painting. And I was getting good at it.

One of the tour stops was to see the terracotta warriors in Xian. As we were leaving the museum, a lady hawker was trying to sell me postcards for $2. In the mindset of negotiating everything, I negotiated hard to get it down to $1. We agreed, but as I got on the bus, she hit me with her postcards for negotiating such a low price. Unfortunately, we left before I could give her more money. This was a serious imbalance in fairness. $2 for her probably was a lot of money, but it was not much for me. If I had thought more about what was fair for her, I would definitely not have negotiated and just given her the $2. I still feel bad about that.